If you’re a fan of craft beers, especially IPAs and wheat beers, you’re probably already used to drinking hazy or cloudy beer. Indeed with the increasing popularity of fresh, unfiltered and unpasteurized beers, more and more consumers have come to accept and even enjoy a bit of haze.

Having said that, the vast majority of beers sold in bars, supermarkets and liquor stores are crystal clear, and if this is the first time that you’ve been served a glass of cloudy beer, you might be worried that it’s gone off or that there’s something wrong with it.

Cloudy beer is nothing to be concerned about. The cloudiness results from protein, yeast and other by-products of the brewing process and cloudy beer is perfectly safe to drink.

As a homebrewer, I’ve grown accustomed to my friends’ comments when I serve them a glass of somewhat cloudy homebrew beer. I’ve got used to explaining that cloudy beer is safe to drink and that commercial beers are only clear because they’ve been filtered and pasteurized.

In this post, we take a look at what makes beer cloudy and what you, as a homebrewer, can do to fix it.

What causes cloudy homebrew beer?

Six main factors cause cloudy or hazy beer:

1. Yeast

Perhaps the most common reason for cloudy homebrew is yeast.

After fermentation has finished, the yeast flocculates, which means that it clumps together in lumps and then sinks to the bottom of the fermenter, where it becomes part of a sediment called trub. When the beer is transferred from the fermenter to a keg or bottles, the brewer tries to leave the layer of trub in the fermenter.

Some types of yeast flocculate better than others. Beers such as hefeweizens deliberately use low flocculating yeast strains to produce intentionally cloudy beer with plenty of yeast in it.

2. Starch in the beer

The first step in the brewing process is called mashing or “the mash”. During mashing, malted grains, mainly barley, are mixed with hot water so that enzymes in the grains can convert starch, also in the grains, into fermentable sugar, which is converted into alcohol later in the brewing process.

As explained in this post, the conversion of starch into sugar takes place within a specific temperature range. If you don’t control the temperature of the mash correctly, then you may end up with excess starch in your beer, making it hazy.

3. Dissolved proteins

In addition to starch, malted barley, oats, and other grains that are used in beer making also contain protein. This protein has two effects on the finished beer.

On the plus side, it helps form and maintain a foamy head on the beer.

On the downside, after yeast, protein is one of the most common causes of cloudy beer.

4. Polyphenols

Polyphenols are a group of chemicals found in both malted barley and hops which react with protein in the beer to make it hazy.

The characteristic haze of New England IPAs comes from polyphenols present in the large number of hops added during fermentation (a process called dry hopping) combined with the yeast strains that are typically used to brew them.

5. Chill haze

Beer may also become hazy if served at very low temperatures, approaching zero degrees Centigrade (32 degrees Fahrenheit). This is called chill haze and is caused by the combination of proteins and tannins in the beer.

Chill haze is reversible and will usually clear up when the beer warms back to the correct temperature.

6. Sediment

Sediment is usually a mixture of yeast and dissolved proteins and can be considered a feature of bottle-conditioned beers.

After fermentation is complete, the brewer siphons the beer from the fermentation into sanitized bottles. They then add a measured amount of sugar to the beer before fitting the cap and leaving it in a dark place to bottle condition for several weeks.

Since the beer wasn’t filtered, it contains yeast which is reactivated by the sugar and creates carbon dioxide that carbonates the beer. Once all the sugar has been consumed, the yeast then goes dormant and sinks to the bottom of the bottle.

Another cause of sediment is hop and grain particles which were transferred into the bottles or keg when the beer was bottled. This can generally be avoided by not disturbing the trub when siphoning the beer out of the fermenter.

How to prevent cloudy homebrew beer

Several things can be done to prevent your homebrew from being cloudy or help minimize the haze.

Mostly they are additional steps that can be undertaken during the brewing process. However, if you’ve already bottled your beer and have found it to be unexpectedly cloudy, there are still a couple of things you can do that will help reduce the haze or keep the floaties at bay.

1. Cool the wort down quickly after boiling

The third step in the brewing process is boiling the wort for sixty minutes. During this time, hop and other adjuncts are added to the wort. At the end of the boil, the wort is cooled down to room temperature before yeast is added.

You should always cool the wort down as quickly as possible. There are two main reasons for this. Firstly, the faster you cool the wort down, the less chance it will become infected.

The other reason for cooling the beer down quickly is to create the hot break, whereby dissolved protein from the mash solidifies and sinks to the bottom of the kettle. As mentioned earlier in this post, protein is a major cause of cloudy homebrew.

I cool my wort using an immersion chiller like this one.

2. Use a different type of yeast

Some types of yeast flocculate better than others. If you find that your homebrew is always cloudier than you hoped, it’s worth trying a different yeast strain.

3. Cold crashing

Another popular way of reducing haze is cold crashing the beer after it has finished fermenting.

Cold crashing is a process whereby you quickly cool the fermenter down to just above freezing point and keep it at that temperature for twenty-four hours or more. This helps the yeast and other particles drop out of suspension.

One thing to bear in mind if you will be bottle condition your beer is that you shouldn’t let the temperature drop below about five degrees Centigrade (41 Fahrenheit). This ensures that there is still some active yeast in the beer when bottled.

4. Take your time

As mentioned above, after fermentation has completed, the yeast flocculates and sinks to the bottom of the fermenter. Even though fermentation is complete, the yeast may not have had enough time to settle out if you bottle the beer too soon. By leaving the beer in the fermenter for a few extra days, you can ensure that the yeast has had enough time to flocculate a clean up after itself. This will both reduce yeast haze and help eliminate undesirable off flavours.

5. Add finings

The word finings refers to products used to prevent cloudiness in both beer and wine. Some finings are added during the boil, whereas others are added to the fermenter.

No matter when they are added, finings work by attracting protein molecules (including yeast cells) to them. This causes the proteins to clump together and sink to the bottom of the kettle and/or fermenter, which helps prevent them from ending up in the bottles or keg.

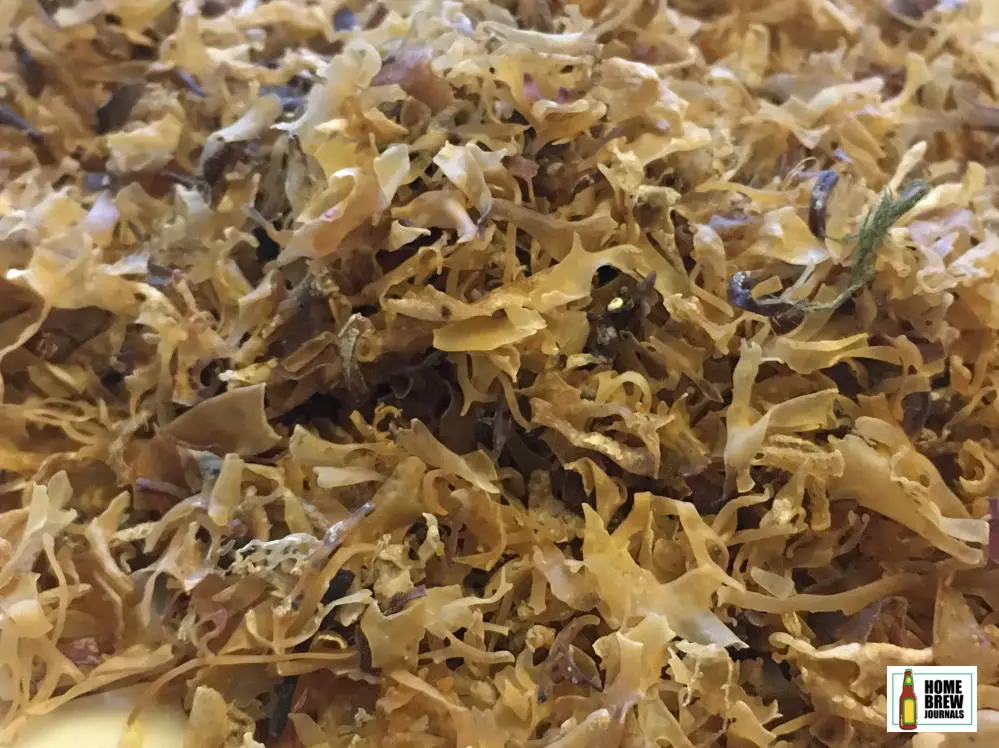

I don’t usually worry too much if my homebrew beer is cloudy. If I want to make a particular beer as clear as possible, I add a teaspoon full of Irish Moss (a type of seaweed) to the wort fifteen minutes before the end of the boil.

You can find out more about beer finings in this post.

6. Store the beer in the fridge

So far, the methods I’ve described are all parts of the brewing process. If you’ve already bottled your beer and have found that the first bottle was cloudy, you could try storing the remaining bottles in the fridge for about a week. This may help the yeast drop out of suspension and sink to the bottom of the bottle.

7. Pour the beer slowly and carefuly

If you bottle your homebrew, then it’s only natural that there’s a layer of yeast at the bottom of the bottle. All bottle conditioned beers, including commercial beers such as Duvel, have a thin layer of sediment at the bottom of the bottle.

The key to serving bottle conditioned beers is pouring slowly and leaving a small amount, including the yeast, in the bottle.

Whenever I give a bottle or two of homebrew to my friends, I always tell them to store them in the fridge, in the upright position for at least twenty four hours before opening them and then pour them slowly into the glass, leaving the last few drops in the bottle.

Conclusions

Cloudy beer is safe to drink, and some beer styles are supposed to be cloudy or hazy.

The haziness is caused by protein, yeast and other chemicals found in hops and malted barley.

There are several things that a brewer can do to reduce the cloudiness, but at the end of the day, the haze is only cosmetic and doesn’t affect the beer’s flavour.